Share This Article

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw is a necropolis that left a huge impression on me. Every time I was in the area, I somehow missed the opening hours-but I finally managed to visit! This cemetery is the second largest in Poland (after the one in Łódź) and one of the largest in Europe.

Location

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw is located in the Wola district. The exact address is Okopowa Street 49/51. The main gate is right at the intersection of Okopowa and Mordechaja Anielewicza streets. There is no dedicated parking lot next to the cemetery. I parked across the street at the Klif Shopping Center. Customers can park there for free for up to 3 hours, so I did some shopping and combined the useful with the pleasant.

You can also get here by public transportation. The stop directly in front of the entrance gate is called “Cmentarz Żydowski” (Jewish Cemetery). Tram lines 70, 71, 73, 74, and 78 stop here, as well as bus 180 (plus night buses N41 and N91, which are less helpful as the cemetery is closed at night). You can also take a bus to the Esperanto terminal, served by lines 107, 111, and 100.

There is another Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, located in the Bródno district. However, in search results and GPS navigation, the Wola cemetery is usually the first one that comes up.

Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw – Entrance, Opening Hours, and Admission

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw is open Monday to Thursday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Friday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., and Sunday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. It is closed on Saturdays (Shabbat), as well as on Jewish and Polish public holidays. The cemetery is owned by the Jewish Religious Community of Warsaw. Entry is possible upon purchasing a donation ticket, which costs 20 PLN per person.

This is still an active cemetery. Out of respect for religious customs, men should wear a head covering. If you don’t have one, you can borrow a “kippah” in the building just past the entrance.

A Brief History of the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw that we’re writing about was established in 1806. The initiative to create it came from the Warsaw Jewish Community, and originally it was called the “Cemetery on Gęsia Street.” It was not the first Jewish cemetery in the city. It followed the cemetery located in the Old Town and the one in Bródno—chronologically, it was the third.

The Chevra Kadisha burial society was founded in 1806, and the first burial took place at the end of that same year. The first person to be buried here was Nachum, son of Nachum from Siemiatycze, who died on December 6, 1806. His tombstone has not survived, but the oldest preserved one is only slightly newer—it dates back to 1807 and marks the grave of Sarah, daughter of Eliezer.

Some sources claim that this cemetery was used exclusively for burying the wealthy, while the poor were interred at the cemetery in Bródno. The cemetery grounds were gradually expanded due to overcrowding.

In 1826, a funeral home was built, but it was destroyed five years later during the November Uprising. It was eventually rebuilt and expanded. In the interwar period, the wooden fence surrounding the cemetery was replaced with a brick wall.

During World War II, many events took place on the cemetery grounds. On the one hand, it served as a site for mass burials and executions; on the other, it became a location where food was smuggled in and where Jews went into hiding. The cemetery suffered damage during the war, but it was not extensive. The most significant destruction came in 1944, when the funeral home and adjacent synagogue were blown up.

After the war, the cemetery fell into neglect and was gradually overgrown with vegetation. It also became a gathering place for the so-called “social underclass.” Fortunately, individuals and organizations stepped in to save the cemetery and continue working to restore and preserve it.

Since 1973, the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw has been listed as a historic monument and is under the care of the Mazovian Provincial Conservator of Monuments. In 2014, along with five other cemeteries in Powązki, it was designated a Historic Monument of Poland (Warsaw – the ensemble of historic denominational cemeteries in Powązki). The cemetery is still in use for burials today.

If you’re looking for more information about the history of Jewish cemeteries and other Jewish heritage sites in your cities, be sure to visit the website sztetl.org.pl.

Entrance gate

The gate through which we enter the cemetery is not the only one you will see on its grounds. Just after passing through the main entrance, you will soon come across a second gate. A sign on it states that this is a historic gate (visible in the photo) from the time of the ghetto (1940–1943). It was restored in 1998 by the “Gęsia” Jewish Cemetery Foundation, with the work funded by Arick and Laura K. Karwasser in memory of the Karwasser family and the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

Current State

Many people consider the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw to be the largest in Europe in terms of the number of matzevot (tombstones). In terms of area, it also ranks among the largest in Europe. There are over 85,000 tombstones on the site, although some sources estimate the number to be over 200,000. Judging by the quality of the available data, the lower figure appears to be more reliable. The cemetery covers an area of 33.5 hectares.

Upon entering the cemetery, visitors pass administrative buildings and the pre-burial house. If you’re looking for a specific grave or person, you can obtain information about them there. In addition to graves, there are also numerous monuments. Not far from the entrance, you’ll see a monument and symbolic grave of Janusz Korczak, whose real name was Henryk Goldszmit. The monument was unveiled in 1982 and depicts Korczak with children from the orphanage he ran.

Each burial quarter is different from the others — varying in the age of the tombstones, their style, the materials used, and also the level of “orderliness.” Most Jewish cemeteries in my region are small. Often, they are so damaged that only a few dozen matzevot remain. The largest ones have a few hundred — and here we’re talking about over 85,000 tombstones! The scale is unimaginable, and I will be impressed by the sheer magnitude of this place for a long time to come!

This cemetery is also a perfect example and gallery of sepulchral art. You’ll find classic sandstone matzevot, familiar from cemeteries all over Poland, but also artistically valuable graves. It’s worth learning the names of the sculptors who created many remarkable artistic monuments here. Among them are Abraham Ostrzega, Feliks Rubinlicht, and Szymon Kratka.

Upon entering the cemetery, I saw many people — which is rare at cemeteries in my home region. Some were strolling, admiring the gravestones; others were searching for unique photographic shots to capture the magic of the place; and still others were volunteers or cleanup crews tidying up after summer storms and winds that had recently hit the cemetery. There was no major visible damage, but I did come across tombstones broken by fallen tree limbs.

Symbols of the graves

Just like in Jewish cemeteries across Poland, this one also features many graves adorned with meaningful symbolism that tells us something about the person buried there. Not all tombstones include symbolic elements, but in some sectors you’ll find quite a few.

What stands out are hands dropping a donation into a charity box, broken trees and candles, hands in a gesture of blessing, bookshelves, or crowns. As you walk among the gravestones, you’re bound to notice them – and each of these symbols carries a specific meaning.

Kielce Connection

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw also has a strong connection to Kielce. While there are certainly more individuals buried here who had ties to Kielce, one person who cannot be overlooked is Mojżesz Pfefer, whose grave is located in plot number 1. He was a long-time member of the board of the Jewish community in Kielce and the benefactor of the city’s synagogue. It was he who donated the plot of land on Nowowarszawska Street and 20,000 rubles for the construction of the temple.

This grave is remarkable not only because of the person buried there — it also features a carved image of the Kielce synagogue, which is truly striking!

Esperanto

While wandering through the cemetery, you may come across a tombstone with a large green star made of mosaic, featuring the letter “E” in the center. This is the grave of Ludwik Zamenhof, also known as Eliezer Lewi Samenhof. Born in Białystok, this ophthalmologist became famous worldwide for creating the Esperanto language. Zamenhof’s goal was to create a language for international communication, one that would not replace any national languages. Today, Esperanto is not recognized as an official language by any country, but according to various estimates, it is spoken by anywhere from 200,000 to around 2 million people worldwide.

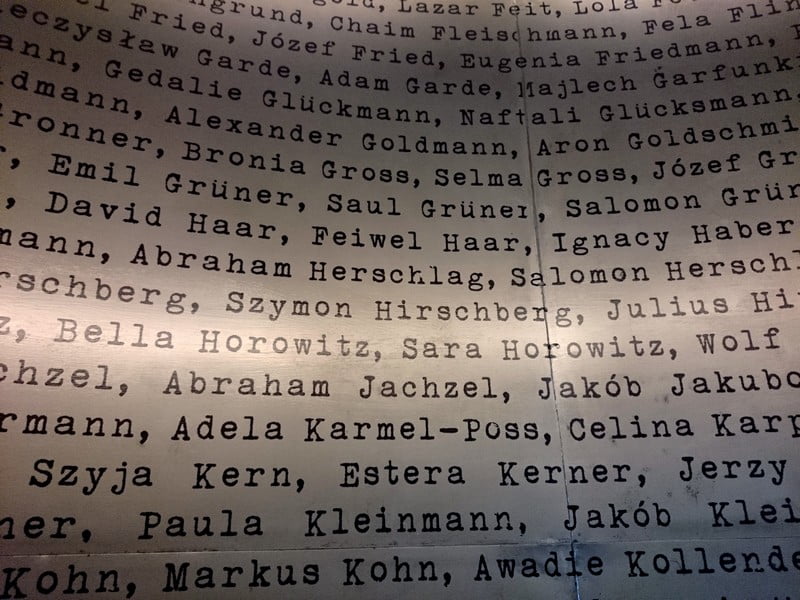

Grave of the Ghetto Victims

While walking through the cemetery grounds, you will come across a unique monument. It was designed by the Archiworks studio and commemorates the mass graves located in the cemetery. These graves hold the remains of Jews who died on the streets of the ghetto. The monument consists of two plots filled with pink quartzite. A total of 350 tons of stones were used to create this monument, symbolizing the thousands of murdered Jews. Between the plots stands a structure made of steel rods, holding stones. According to the creators, it is meant to evoke a shattered column, symbolizing a life cut short.

Is It Worth Visiting the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw?

The Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw made a huge impression on me! If you are interested in this subject, be sure to add it to your list of places to visit! The first thing that surprises you is its size – you can walk around it for several hours. The second aspect is its diversity – you will find both simple tombstones and elaborate grave monuments. The third thing that sets this cemetery apart from most pre-war cemeteries is the fact that many inscriptions and writings on the graves are also in Polish, which makes searching easier and also gives a completely different experience compared to Hebrew inscriptions, which many people do not understand.